Manufacturing curious moments

“You never answer our questions!” a student proclaimed to me

just this morning. He continued by saying “It’s half good for us, but also half

infuriating!”

Another student chimed in “Well, he does kind of answer us…

but usually by asking more questions.”

This is something that I have been very deliberate about this

year, and it has been very challenging. Whenever a student asks a question,

before I answer, I always consider the following: is this student asking this

question so that they can stop

thinking or keep thinking? If it is

the former, then I never answer, I usually just ask a question back in order to

get them to reflect on what they really want to know.

Teachers can spot these stop thinking questions but sometimes it would be so much easier just to answer them. For the benefit of the learner, we have to resist.

“Is this right?”

“Is this good enough?”

“Will this be on the test?”

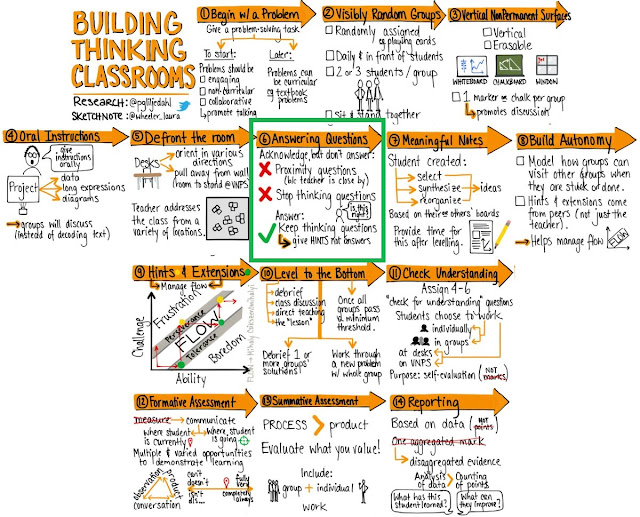

Based on Peter Liljedahl’s research on thinking classrooms, I have found that if I stop answering these types of “stop

thinking” questions, students are quite observant and learn to stop asking

them. Instead, they ask more questions related to the task or problem; they

notice that good questions lead to good hints.

This morning, we were in the middle of reviewing for the

final exam (in random groups) and a group of four friends were lamenting that they

have never all been in the same group since the beginning of the year. They wondered

out loud what the probability was that they would be randomly grouped together.

“Why are you thinking about that right now, it’s not going

to be on the exam.” one student said.

“I have to find out! We have 16 minutes, let’s figure it

out.” said another.

As the teacher, I could have directed them back on task of

preparing for the final exam, I could have given them the answer, or I could

have told them to wait 3 years until grade 12 when they will learn about

combinations and permutations.

Instead, I dropped a subtle hint to anchor them in a prior

learning experience. “Is this anything like counting handshakes?”

Off they went and found out the probability before class

ended.

I like to think that the kind of curiosity that the students showed this morning was a result of a school year of manufacturing other curious moments and

helping the students navigate them. As a teacher, it is what we strive for – learners who

are so engaged that they just have to

find out how things work.

However, curiosity is a fragile thing. Todd Kashdan, a

speaker I saw at the Learning and the Brain conference is a researcher in the

psychology of curiosity. He spoke about curiosity as not just the desire to explore something new but that it had to be balanced with a self-efficacy and belief that

we can handle this new thing.

The man in this picture encounters this situation where

there is an unknown but the result isn’t curiosity – it is fear.

It is tricky to balance the unknown with the feeling that the unknown will not be overwhelming. How do we manufacture these moments of curiousity in the classroom? How do we create an environment that is safe to take risks? Always having an anchor to something that is known is a good start.

This usually comes in the form of a diagram, a story, or access to prior knowledge of a connected concept. The students that wondered about probability this morning anchored onto the idea that counting handshakes and grouping pairs of people was connected to counting groups of four. This created a curious moment that lead to some quality learning.

It is tricky to balance the unknown with the feeling that the unknown will not be overwhelming. How do we manufacture these moments of curiousity in the classroom? How do we create an environment that is safe to take risks? Always having an anchor to something that is known is a good start.

This usually comes in the form of a diagram, a story, or access to prior knowledge of a connected concept. The students that wondered about probability this morning anchored onto the idea that counting handshakes and grouping pairs of people was connected to counting groups of four. This created a curious moment that lead to some quality learning.

By the way, they figured there was a 0.002% chance that they will be randomly grouped together. Not very likely.

Comments

Post a Comment